Quantifying Anger: How I Started Measuring Frustration

- Armands Sakne

- Oct 28, 2025

- 2 min read

Updated: Nov 7, 2025

In field service, emotions are data. You just have to learn how to read them. After years of visiting customers across Europe, I noticed a pattern. The most frustrated users were often the ones with the highest potential. Their machines were not broken. Their expectations about machine were.

At first, I tried to fix everything technically. Gas flows, software bugs, consumable consumption. But frustration did not disappear. It only changed shape. That is when I realized that the real error was not in the machine, but in the infrastructure around it.

During many visits I also discovered that most customers lacked even the basic understanding of plasma cutting technology itself. They could operate the CNC, but not interpret what the arc was doing. No one had ever explained to them how current, gas balance and torch height interact to create cut quality. In that knowledge gap, frustration always grows.

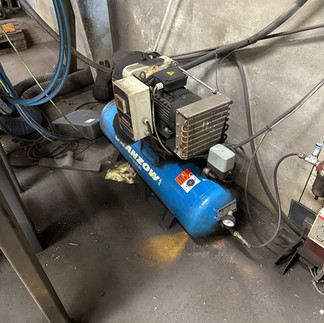

A few years ago, I visited a customer who had been struggling for years with an HPR400XD system. He was using an 80-liter piston compressor to feed a high-precision plasma unit. The results were, of course, terrible.

Absolutely not suitable for a high demand plasma system like the HPR400XD. As minimum air supply must be at least 200l per minute.

From the customer’s perspective, the emotional conclusion was simple:

“This machine is sh*t.”

On paper, all specifications looked perfect, powerfull plasma unit, new torch and consumables.

But in real operation, the following quantitative process issues were identified:

Insufficient air supply — both in pressure and total flow volume.

Plasma arc voltage instability — constant fluctuations due to pressure drop.

Incorrect kinetic and thermal arc behavior — distorted arc shape and energy density.

Misleading voltage readings — plasma arc voltage not representing true arc potential.

Thickness limitation — unable to cut materials above 30 mm due to low arc energy.

Bevel deviation — torch height control reacting to false voltage signals, causing random arc voltage readings. Constatnly changing plasma arc density.

I simply reconnected the machine to the main factory air line that came from a large screw compressor with a proper dryer and cooling system. The difference was immediate.

After stabilizing air pressure with a screw compressor, the T-Index jumped from 70 → 86, equivalent to a 23% performance improvement.

Cut quality, process stability and consumables life all improved within 1 day.

The parts you see in the pictures below show what HPR400XD with a bevel system can really do when supplied with clean, stable air.

The next year, the customer bought a new screw compressor with a 300-liter receiver and a refrigerated dryer. That single change transformed his production.

Today, when I hear that there is a customer with an HPR or XPR system and “nothing works,” I know it will be an interesting visit. Because those are the moments when you can literally see frustration turning into understanding. And nothing is more satisfying than watching a customer go from angry to proud of their machine again.

Over time, these moments and the data behind them evolved into a structured framework that I now call the T-Index. It measures not only hardware precision but also how people and organizations use that precision. Because you cannot manage what you do not measure. Especially when the problem looks emotional.

Comments